I saw you emerge onto the dead bird app and proceed to get into a couple of school voucher related flaps, and I found myself in the not-unusual position of wanting to say something and being too lazy to boil it down to tweet-sized construction ("Too lazy to tweet about it" would make a good sub-heading for this blog). I'm going to give it a whack here, in part because you are my favorite kind of education writer: not ideologically blinkered. not paid to have a particular opinion, and more interested in light than heat. Also, we only agree some of the time.

My impression is that you see a lot of the debate over vouchers as being tied up with people over-interested in devotion to their particular team, and that's a valid critique of some arguments out there. And I think you often capture nicely the gulf between arguing over good state policy and trying to decide what's best for your own kid.

Watching you talk about what's wrong with the voucher debates challenges me to go back and rattle around in my own skull to think about what my objections to vouchers are. For what it's worth, here's some of where I land.

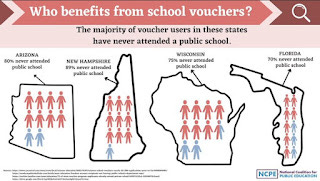

In particular, you had a reaction to someone tossing this well-worn graphic up:

Your response was

And why is this a problem? The idea that children should have to sacrifice a year of their schooling years as some kind of "purity" test is more about serving adults than children.

I agree that there's some no-zero number of parents who are scraping to get their kid into private school. If Tennessee goes the way of Iowa and Florida and sees vouchers followed by tuition increases, the voucher won't really help those parents, but it won't hurt them, either. This is definitely one of those places where the personal and policy perspectives are different animals. Will universal vouchers widen the gap between rich and poor? Almost certainly. But it's not fair to make that an individual parent's issue to solve.

The universal vouchers for students already in school creates a taxpayer problem, because it increases the number of students that the taxpayers pay for. Taxpayers are paying for 100 students at the public school. 10 leave for a private school. 25 already at the private school get a voucher (and why wouldn't they? what sense does it make to turn down free money?) But now taxpayers are paying for 125 students. If that money comes from the school of origin, that school can either cut programs or raise taxes. Universal voucher programs get really expensive, really fast.

One of my objections to choice in general and vouchers in specific is that policymakers aren't willing to be honest about the cost, but instead lean heavily on the fictions that A) money doesn't matter in education and B) we can run multiple school systems for the same money we're spending now.

Even if I accept that vouchers are a benefit to families (and there are plenty of reasons to debate that), they are a benefit that is only available to some. Every voucher system in this country holds sacred the providers right to serve only those they want to serve. Families can be rejected or expelled because of religious beliefs, being LGBTQ, or having special needs. In Pennsylvania, we've got a voucher school that reserves the right to reject your kid for any reason AND to refuse to explain why they've done it. Plus, of course, the financial barriers still in place for the priciest privates.

And so somehow we end up with a government benefit that is only available to some people, and that availability is decided on the basis of such criteria.

That points to what I find most problematic about the voucher movement, which is the implicit attempt to change the whole premise of education in this country. Instead of a shared responsibility and a shared benefit, we get the idea that education is a private, personal commodity. Getting some schooling for your kid is your problem. From there it's a short step to the idea that paying for it is also your own problem and not anyone else's.

Do I think that we'll ever see Milton Friedman's dream of a country in which the government has nothing more to do with education than it does with buying cars? Probably not, but I'm less confident than I was a decade ago. I do think we will see in some states a public system that is shrunk down, if not down to drown-it-in-the-bathtub size, to something small and meagre and basic. And we have right now states working on the DeVos vision of kids who mostly work, pick up a couple of courses on the side, and that's good enough. So probably not the end of public education entirely, but a new multi-tiered system of very separate and very unequal education providers.

The irony for me has always been that I can imagine a system of school choice (see here and here) but the modern reform movement of charters and vouchers strikes me as headed in a completely different direction, making a lot of worthwhile promises that it does not particularly try to deliver on.

See, this is why I don't tweet more. I reckon you mostly know this stuff, but once I start, I have to work all the way through.

I hope people subscribe to your fine substack and avoid saying silly things to you on the tweeter (charging you with being a Lee shill was an extraordinary reach). Stay safe and warm.

Another issue with access is geography. If you live in a more rural area, the only way you can access voucher schools is if your parents can transport you to and from every day. In Wisconsin, vouchers are currently income limited. Lower income people in urban areas use them, but not much in more rural areas. If they were to become universal here, the higher income rural families would access them but not the lower income families because for most of them, daily transportation would be a hurdle. It would be interesting to look at states with universal vouchers and how enrollment varies by location as well as income.